Mildred Chapin Fox was born February 6, 1906, in White Hall, a small prosperous Illinois town. Her mother, Ella Leona Chapin Fox, was the daughter of a school teacher who became the town’s first mayor and owner of the White Hall Chair Manufacturing Company. Mildred’s own father was John Henry Fox, the foreman of the chair company who later opened J.H. Fox & Co., the town’s furniture store and mortuary.

Mildred was graduated from White Hall High School in 1925. Her much older brother, Clarence, was a partner in their father’s undertaking business until his death in 1920 of influenza. During Mildred’s second year at Illinois Women’s College her mother died. Mildred transferred to Northwestern University where she earned a Fine Arts degree in 1928 and chose to return to her father’s home and to teach at White Hall High School.

Mildred’s earliest known but undated painting is a watercolor of two women in sunbonnets, carrying baskets and waiting for a ride across a body of water, possibly a seascape in Holland. Her early interest in art was encouraged by paintings on canvas and ceramics by her mother, her cousin Lucile and her mother’s sister, Edith Chapin.

One morning in 1930, when she went to her father’s bedroom to wake him she found that he had died in his sleep. Days later Mildred’s boyfriend, John Arnold—they had met a few years earlier during a high school track meet in nearby Roodhouse—served as a pallbearer at her father’s funeral.

Mildred decided to move next door to live with her Aunt Edith Chapin. In June, she and John were married and moved briefly to Bloomington, Illinois, where John was a teller at the Corn Belt Bank. They moved to Norman, Oklahoma where John took courses at the University of Oklahoma to complete undergraduate requirements and pursue his dream of becoming a lawyer.

Colorado studies

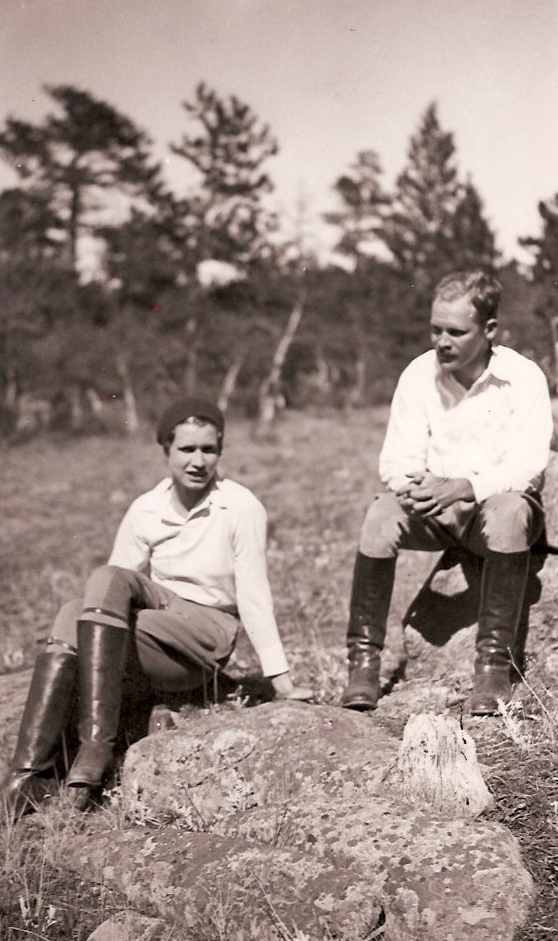

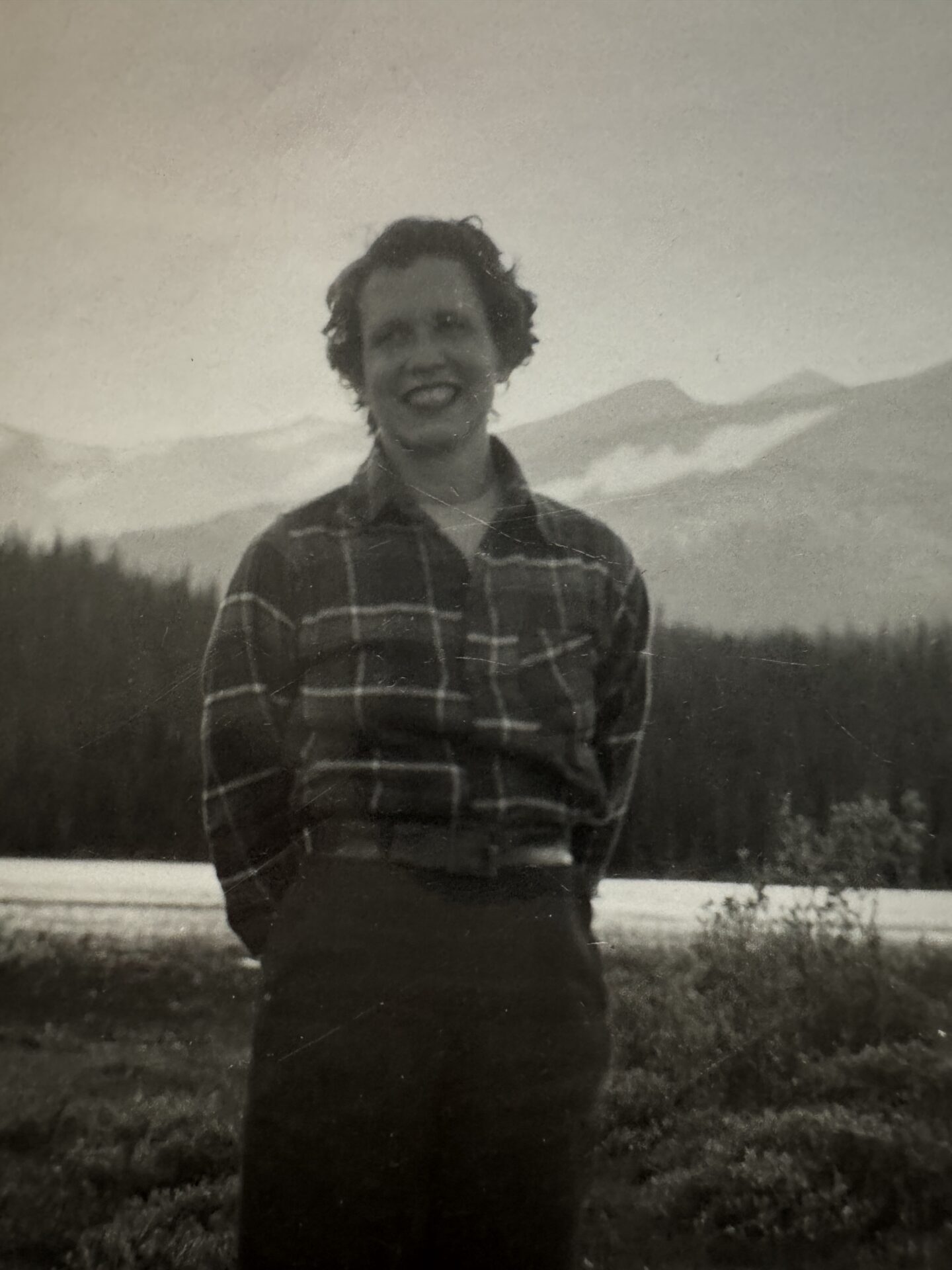

In the Fall, John began classes at the University of Colorado Law School at Boulder and Mildred pursued university studies in life drawing, landscapes, still life, commercial and theater stage design. She studied and practiced all media and produced dozens of class assignments in pen and ink, charcoal, watercolor and oils. Her wood block print, “Steelworkers,” was reprinted in 1933 in RHO, a magazine of the school’s honorary arts society, Delta Phi Delta. In their years in Boulder she and John took every opportunity to hike and picnic above Boulder Canyon. Mildred carried with her a sketch pad, pencil and charcoal.

She recalled many years later that John’s waders, hunting jacket and shotgun, the subject of her early still life oil, “Hunting Clothes,” stood undisturbed in a corner of their Boulder apartment until John completed law school.

“I really worked at that stuff. A lot of the time it was because I loved your father so. And he loved my work.”

Mildred Fox Arnold

“I really worked at that stuff,” she said. “A lot of the time it was because I loved your father so. And he loved my work.”

The University of Colorado’s new art department chair, Muriel Sibell, had recently been hired away from the faculty of New York’s revolutionary Parsons School of Design. Sibell became a friend and mentor to Mildred’s art studies. Mildred was invited by Delta Phi Delta to join Sibell in representing the school’s arts program during the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago.

Industry and manual labor became popular themes in her work during the 1930s Depression. Those hard economic times led Mildred to produce variations of her worker series during her three years in Boulder. “Industry,” more variations on “Steel Workers,” and a large-format book of pen-and-ink illustrations and a hand-lettered portion of Carl Sandburg’s poem, Smoke and Steel, fulfilled some of her graduate school requirements. The family has no record that she completed or received a Master of Fine Arts degree.

Settling in St. Louis

“Paint anything you want. Leave the dishes.”

John Arnold

The couple moved to St. Louis in 1933 where John began his law practice. Mildred’s studio was their small midtown apartment at 5435 Cabanne Avenue.

Her next still life was “Rod and Creel,” an oil study that occupied their dining room table for more than a month. John didn’t complain about the clutter of the artist. He encouraged her desire to paint. “Paint anything you want,” he told her. “Leave the dishes.”

She submitted “Hunting Clothes” to an exhibition of “Oil Paintings of St. Louis and Vicinity” in May, 1934. She wrote boldly on the entry form tacked on the back of the frame, “NOT FOR SALE.” She also began to explore their St. Louis neighborhood with easel and paints and discovered her next subject, a small church cemetery. “I’d go out and take my lunch,” she recalled 40 years later. “It was a little cemetery and I’d sit on a tombstone to eat my lunch. In those days you could do that because not many people painted German churches. That’s the way it looks but it’s kind of modernistic.”

In January, 1935, her “German Church” appeared in a juried national exhibition at the St. Louis Art Museum. The daily St. Louis Star-Times reproduced the oil painting and the accompanying newspaper article identified Mildred among nine St. Louis artists and 40 “nationally known artists invited to exhibit” at the Annual American Show.

The museum’s senior lecturer told Mildred she was preparing to give a walk-through presentation on the winning entries. “I told her I had a picture in the show and I was going,” Mildred later recalled. “Silly fool, I should have kept quiet. I might have learned from her. Instead, I heard very nice things. It didn’t amount to much as far as criticism is concerned,” testimony to her impatience to improve her painting skills.

A St. Louis art critic said her painting had the “rarefied quality of stained glass.” Another called it “bleak and austere, in dull and sharp grays.” A third review described the colors as “faded red and oyster gray, executed with perspective askew in the modern manner.” Five months later the museum exhibited another of Mildred’s oils, “Pot of Tulips,” but she listed it “NOT FOR SALE.” Mildred gave it to her mother-in-law, Ellen Arnold, in Bloomington.

Moving to the suburbs

With the birth of two sons, the young family moved to a house at 526 Ridge Avenue in the quieter southwest St. Louis suburb of Webster Groves where John commuted by streetcar to his downtown law offices. With the birth of a third son, the family moved to a larger house in Webster at 521 Oakwood Avenue.

Mildred and John lived there for the rest of their lives except for two occasions during World War II when John served as commanding officer of a U.S. Navy Armed Guard Detachment on a Liberty ship in the South Pacific. Mildred and the children briefly joined him during his initial training in Gulfport, Mississippi. After his Pacific duty, the family lived in a farmhouse at Camp Peary, a US Navy base in Virginia where John was the Discipline Officer.

After the war when John’s St. Louis law practice began to flourish and their sons grew, the couple became active in civic, social and church activities in Webster Groves and in St. Louis. As a consequence, Mildred’s painting ambitions became secondary to family and community responsibilities.

Late in the summers of the 1950s Mildred experienced rare opportunities to concentrate on painting during family vacations in Eldora, Colorado. The former silver mining town, fondly called Happy Valley by summer residents, was above Boulder and served as the gateway to the glacier-fed lakes of the Rocky Mountains.

Mildred packed an assortment of turpentine, linseed oil, brushes, palette knife, pencils, sketch pads, canvas and a bundle of various tubes of colors—from Cerulean blue to burnt Umber—in a steamer trunk alongside the boys’ fishing rods, tackle boxes, cowboy hats and hiking boots. The family of five shipped their trunk to Rollinsville’s Railway Express Agency at the East Portal of Colorado’s Moffat Tunnel and drove their Ford sedan from St. Louis to Boulder—stopping to visit with Sibell who had married a professor of English, Francis Wolle—and then to collect their trunk for their Eldora vacation.

While John corralled the boys for day hikes and fly-fishing in the roaring streams, meadows and lakes below Arapaho Pass, Mildred wandered through Happy Valley filling sketchbooks with pencil, watercolor and charcoal studies of alpine flowers, mountains and the weather-beaten shanties that were central to Wolle’s timberline aesthetic. Back In Webster Groves Mildred completed several oils during the 1950s. Two were marked for sale at $30 each at the 13th Annual Missouri Exhibition at the St. Louis Art Museum: “Bottles” and “Flowers on a Chair.” Fortunately for the family, neither was sold.

Return to school

How long, how long, in infinite Pursuit

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Of This and That endeavour and dispute?

Better be merry with the fruitful Grape

Than sadden after none, or bitter, Fruit.

John was 56 years old when he died of cancer. Their sons were getting married and starting families and careers of their own. “Cats” and others of Mildred’s paintings graced the walls of her Oakwood home along with “German Church,” but much of her Colorado work was relegated to upstairs bedrooms and their large attic. Her living room bookshelves held small family heirlooms and books with notable illustrations: a Lakeside Press limited edition published the year she was married of Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick” with woodcuts by Rockwell Kent; a copy of the poems of “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam” with sensuous line drawings by Edmund J. Sullivan which was a gift from John on their third anniversary; and a signed copy of Wolle’s 530-page richly illustrated 1949 history of the ghost towns and mining camps above Boulder titled “Stampede to Timberline.”

Mildred earned teaching credentials at Washington University and began teaching English literature and art in Webster Groves High School classrooms her sons had attended. She also qualified as a docent at the St. Louis Art Museum. During years living alone and surrounded by young grandchildren, old friends and neighbors, Mildred had quiet time to study and work at the easel. She bought a seven-foot easel and turned a large empty bedroom of her home into a studio.

Drawings, Life Drawings, and Sketch Diary from various times at school.

As teacher, docent and painter, she attended art lectures and took precise notes on composition—Mondrian’s balance of unequal by equivocal oppositions and the cubism in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. She filled unused pages of a son’s college notebooks and the blank pages of her own old sketchbooks where she discovered a few random scribblings of her children. Mildred also took art lecture notes on the backs of some of her unused Webster Groves High School attendance sheets.

St. Louis exhibits

“I’m not an artist, I’m a painter.”

Mildred Fox Arnold

“I’m not an artist,” she once corrected an admirer of her work. “I’m a painter.”

Her note-taking led her through studies of composition, movement, the works of Wassily Kandinsky, Washington University art department chair Lyonel Feininger, and America’s newer painters, Jasper Johns, Mark Rothko, and Robert Rauschenberg, while she discovered her own path from the representations popular in the 1940s to more abstract oils.

“Poetry, subtlety, and modest restraint. A most finely adjusted composition… Her design elements include transparent bottles with interlocking volumes in depth and leafless tree branches tracery, almost as abstract as her spare arrangements of harvested grain and pyramidal groupings of houses climbing a hill. Her style is strongly her own.”

Published account of the Monday Club show

She exhibited “Bottles” and “Winter” at Webster Groves’ historic Monday Club. A published account of her show described it as “poetry, subtlety, and modest restraint” and a “most finely adjusted composition… Her design elements include transparent bottles with interlocking volumes in depth and leafless tree branches tracery, almost as abstract as her spare arrangements of harvested grain and pyramidal groupings of houses climbing a hill. Her style is strongly her own.”

A very small red house on the hilly landscape of “Winter” reveals Mildred’s need for at least a hint of rich color in the grayest of scenes. She was asked to recreate from a 1969 black-and-white photographic print a wintry hamlet on the banks of the Missouri River. Despite a request that she paint it only in black and white, she was compelled to draw attention in “Missouri River Town” to paint a waving couple walking to the river’s edge. Mildred dressed the woman in a blue dress and the man in a red coat.

Beyond borders

Having never traveled abroad, Mildred joined a 1967 Cook’s Tour to admire Reubens, Holbein and Rembrandt works in the British Museum, walk the corridors of the Scottish National Gallery and travel a European circuit from Copenhagen to Athens. In Rome, she joined a high school faculty colleague aboard the Stella Maris sailing to Crete, Rhodes, and Istanbul to view the vast architectural riches of St. Sophia, the Blue Mosque, and the Topkapi Palace. They returned via Delos and Mykonos, adding 11 days in Rome, Florence, and Venice, and a final four days in Paris.

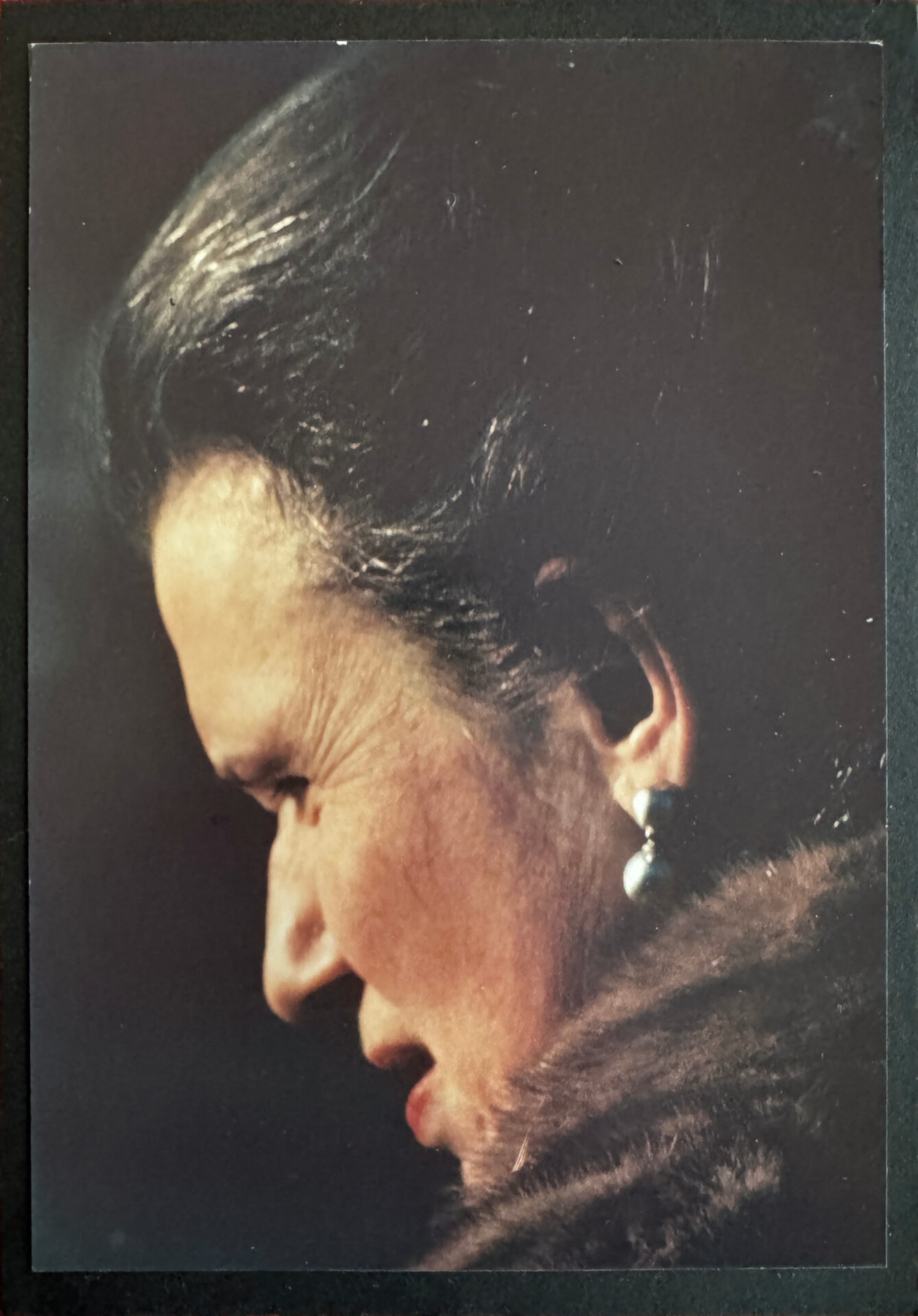

Five years later she flew to Paris to board the luxury liner Renaissance for a 20-day cruise of the fiords of Sweden and Norway. She joined the captain’s table for cocktails as they crossed the Arctic Circle, passing Russian cruise ships as the Renaissance sailed to Skarnaq, misty Narvik, Hammerfest, Bergen, and Le Havre. During one of those journeys, her travel companion, Dorothy Daniels, told her that one of their fellow travelers mistook Mildred for a member of the British royal family.

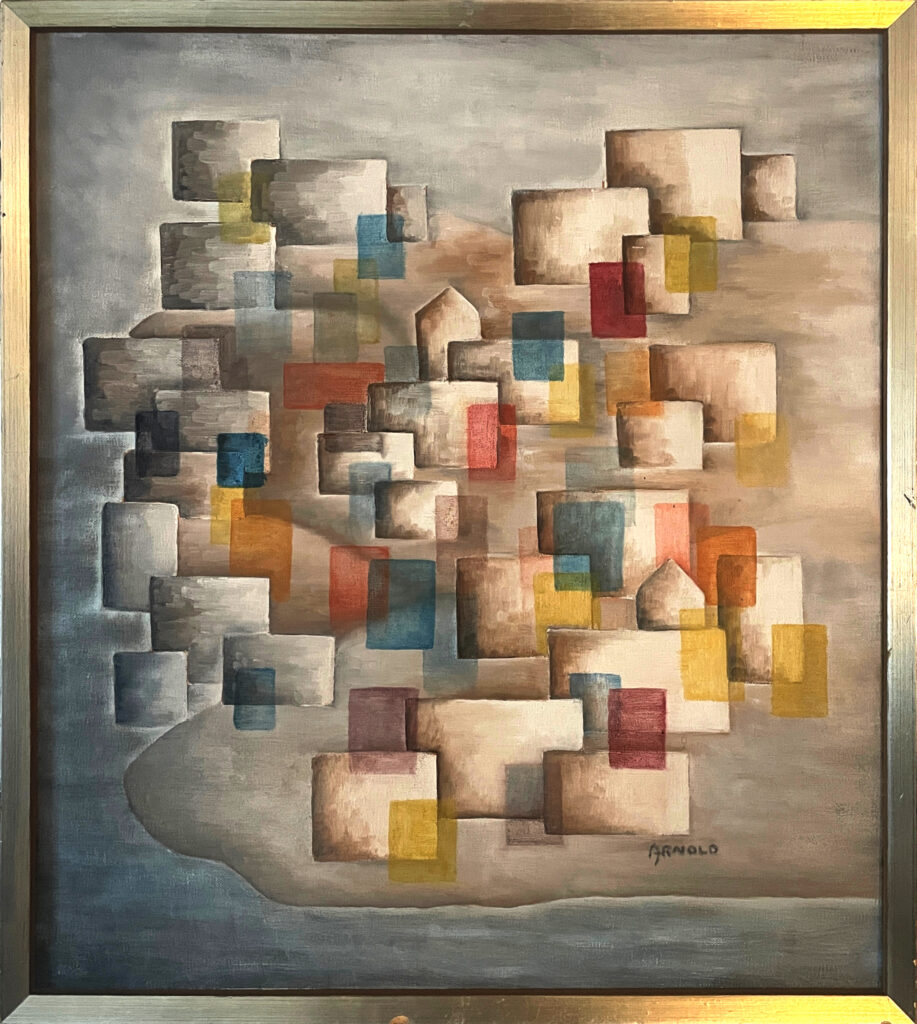

While still teaching at the high school, Mildred was invited to join Group Twelve, a dozen St. Louis artists and designers—among them the Rev. William E. Doyle, S.J., George and Lorraine Gergeceff, Murial Braeutigam and Natalie Liebmann—who met each week for studio work and discussion to continue their professional development. One of her oils, “Boy on Stool,” was produced during this period. Group Twelve held a 1964 exhibition of their work at Ursuline Art Gallery in nearby Kirkwood, Missouri. Mildred exhibited four oils: her 1935 “German Church” and three recent works, the abstract still life ”Bottles,” “Italian Wheat,” and “Structures,” which has been described as houses that are “climbing a hill.”

These last two oils are based on her two extended travels to Europe. “Structures” is an abstract landscape of Hammerfest, a town rebuilt after the Nazi occupation and Russian bombing of the seaside town during World War II.

Last days

“But I am not modest now. Not anymore.”

Mildred Fox Arnold

In the summer of 1976 Mildred was being treated during the final stages of cancer at St. Luke’s Hospital. Her children had hung several of her works in her hospital room: “Bottles,” “German Church,” and “Mykonos,” which may have been her last completed oil painting. One day she asked for a pencil and wrote her name and the year date in the lower corner beneath clusters of Payne’s gray and Sienna color blocks, with doors of transparent yellow, red, green or blue. She thought of adding another color but decided against it. On another morning she described a new idea for a still life of stoneware.

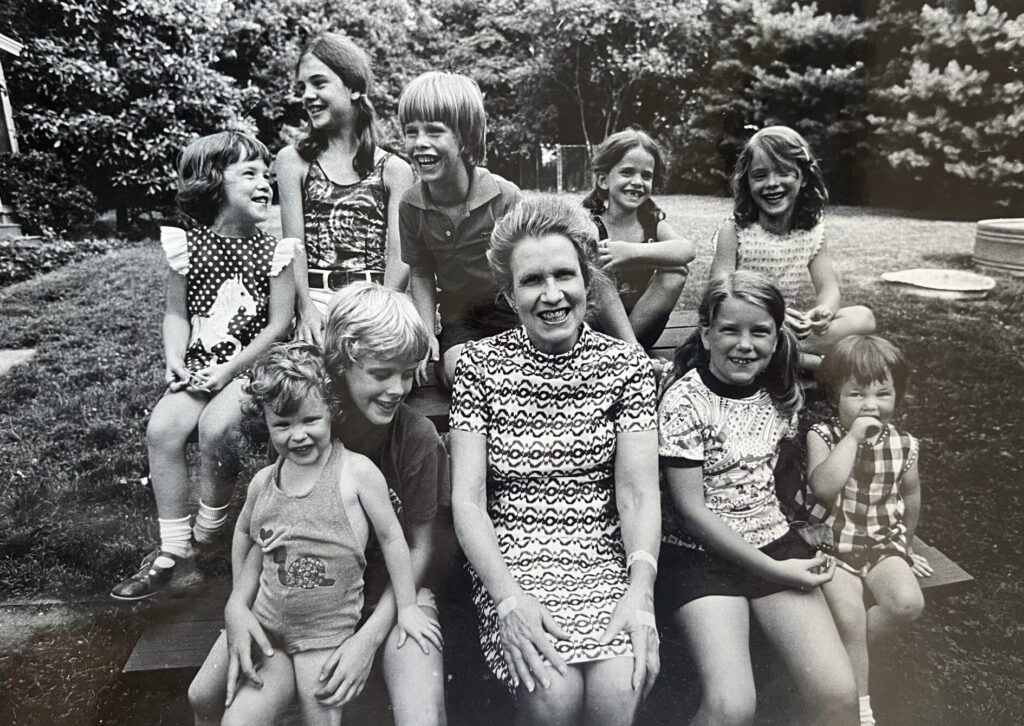

Her hospital window overlooked the rooftops of the St. Louis Art Museum where four decades earlier she had overheard a curator’s praise of her “German Church” and where she more recently had served as a museum docent. Sunlight flooded her hospital room and the lower window was cranked open to a warm summer breeze. When any of her nine grandchildren came to visit, Mildred liked to turn their attention to the view of the museum where sunlight flashed on the tops of cars parked around the statue of Saint Louis mounted on horseback and holding his sword aloft.

She talked about her paintings with one of her sons during a final visit: “I’ve never really given you anything in my lifetime. I thought, ‘Oh dear, they’ll have to hang it.’

“But I am not modest now,” she said. “Not anymore.”

Despite her devotion to the welfare of her family and her community, Mildred persistently developed her skills and her unique and evolving artistic vision and eventually came to terms with her accomplishments.

“I really do like some of the things I’ve done. That’s the reason I haven’t burned them. I thought of it as a legacy.”

Mildred Fox Arnold

“I really do like some of the things I’ve done,” Mildred said. “That’s the reason I haven’t burned them. I thought of it as a legacy.”

Over the past 50 years her art in all of its forms has been displayed in more than a dozen homes of children, her nine grandchildren and her 13 great grandchildren from Washington, D.C. to California. Her family has digitally gathered and created a virtual gallery of the artistic legacy of an American painter, Mildred Fox Arnold.